Treating types of cancer with CAR T-cell therapy is expensive and inconvenient, but a streamlined approach that creates the therapy within the body could make the intervention cheaper and easier

By Carissa Wong

19 June 2025

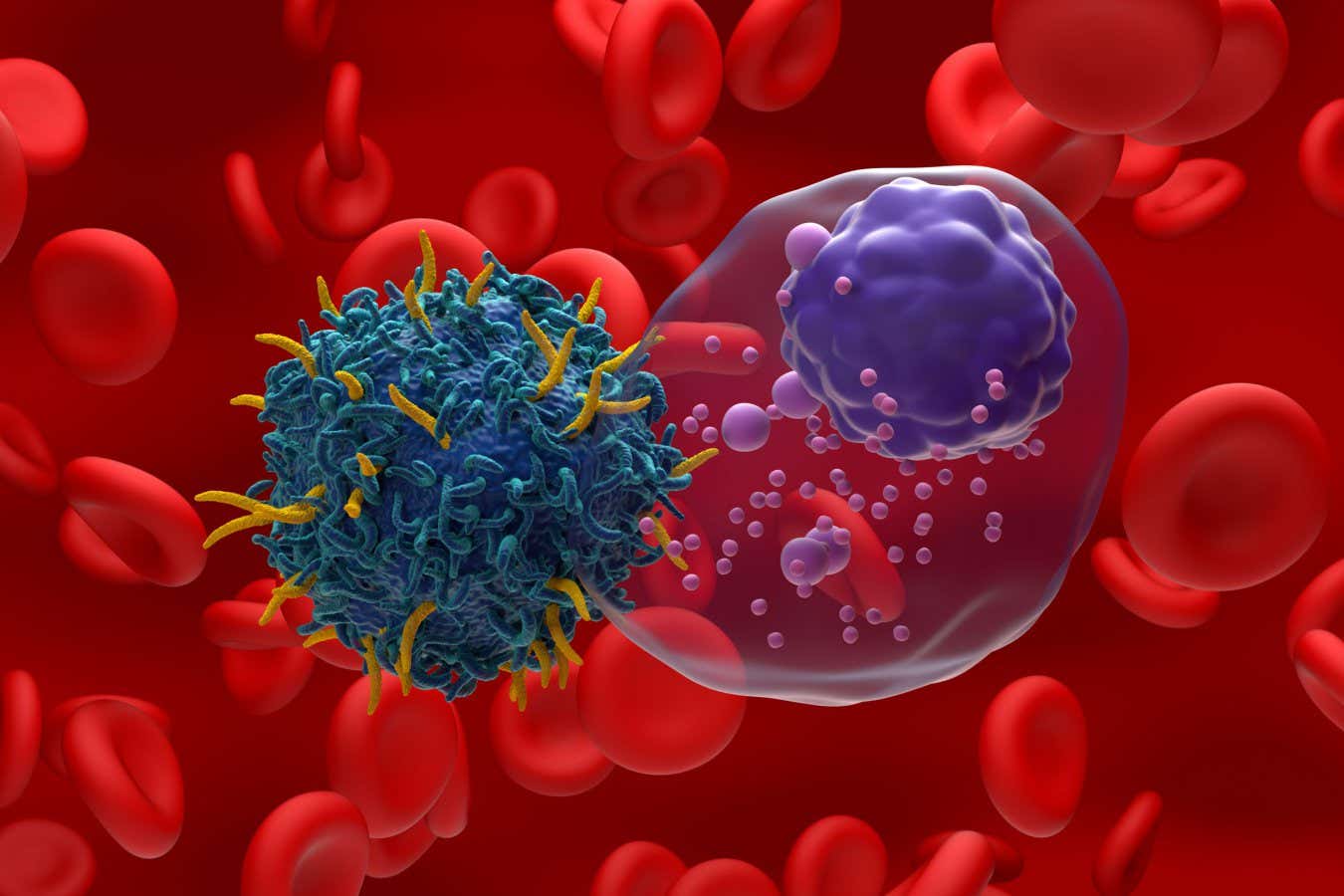

Illustration of CAR T-cell therapy targeting multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer

Nemes Laszlo/Alamy

CAR T-cell therapy has the potential to revolutionise how we treat certain types of cancer by genetically engineering someone’s own immune cells to attack the disease – but it is also cumbersome and expensive. Now, scientists have managed to create the bespoke therapy inside the body of non-human animals, which could simplify the process, driving costs down.

The treatment is mainly available in countries including the UK and US for some people with various types of blood cancer, including some types of leukaemia, where B-cells, a part of the immune system, grow uncontrollably. In these cases it involves collecting a sample of immune cells called T-cells from the blood of a patient and genetically engineering the genome within those cells to permanently target and kill B-cells. These engineered T-cells are then multiplied and infused back into the body.

Read more

We are finally improving prostate cancer diagnoses – here's how

Advertisement

But this process takes time. “You’ve got to take blood, ship it to a central manufacturing lab and then return [the T-cells],” says Carl June at the University of Pennsylvania. “That means it’s very hard to scale up.” It can also cost upwards of $500,000 per patient.

To develop a more efficient approach, June and his colleagues turned to genetic molecules, in this case RNA, that carried instructions to make a protein that recognises B-cells. They packaged these molecules into fatty capsules, which were coated in a protein that allows them to get into T-cells, which then gain the ability to recognise and destroy B-cells. This effect is only temporary, however, as the RNA code remains in the T-cells for about a week before degrading.

Putting their approach to the test, the researchers infused cancerous human B-cells and healthy human T-cells into mice that had been bred to lack an immune system. One week later, they injected the animals with five doses of the fatty capsules across roughly two weeks, with some mice receiving higher doses than others.